Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

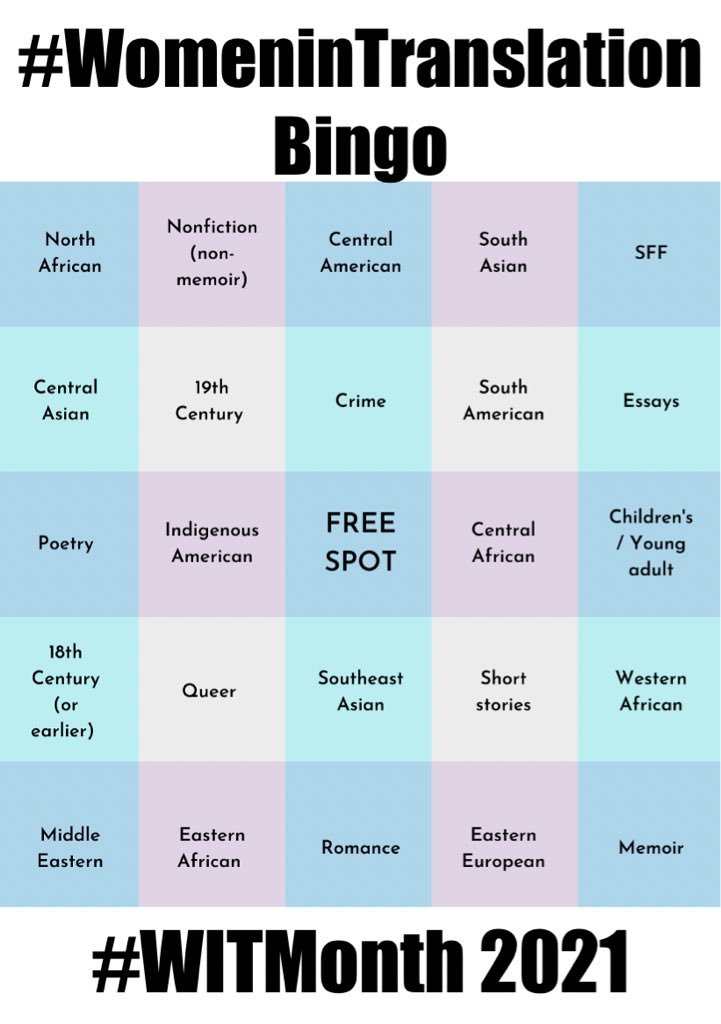

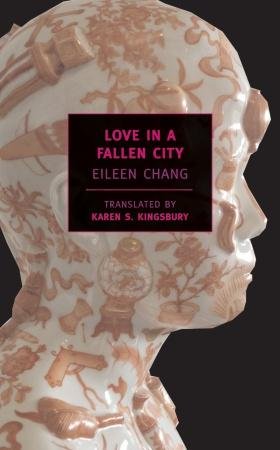

For Women in Translation Month, I'm reviewing three novellas right here on this blog, as well as tweeting poetry in translation daily. The first of the three novellas is "Love in a Fallen City" by Eileen Chang. Stay tuned for a selection from Alexandra Kollontai's Love of Worker Bees and Marguerite Duras' "10:30 on a Summer Evening."

Eileen Chang has long been on my to-read list. So when I learned about Women in Translation Month I put her at the top of my agenda. You may know her through Ang Lee's adaptation of her 1979 novella Lust, Caution. Born in Shanghai in 1920, she straddled two radically different worlds. Translator Karen S. Kingbury writes in her introduction to Love in a Fallen City that "Chang's worldly form of the sublime was achieved [...] by viewing her father's [aristocratic, traditional] Qing world from her mother's [modern, Edwardian] perspective, but with an artist's compassionate detachment." This straddling of eras is apparent from the start of "Love in a Fallen City." Liusu, a twenty-eight-year-old divorcee, struggles to live with her stifling family in Shanghai. Their clocks are literally one hour behind the rest of the city to "save daylight," and, "The Bai household was a fairyland where a single day, creeping slowly by, was a thousand years in the outside world."

When news of her ex-husband's death arrives, her family tries to convince her to return to his family as his widow--thus relieving themselves of her burdensome presence. Rather bleakly, her elderly mother says, "Staying with me is not a feasible long-term plan. Going back is the decent thing to do. Take a child to live with you, get through the next fifteen years or so, and you'll prevail in the end." A matchmaker suggests Liusu find a new husband or become a nun and eventually convinces the Bai family to allow Liusu to travel with her to Hong Kong. There, the major conflict unfolds, when it becomes clear that Fan Liuyuan, "an overseas Chinese" had contrived to have Liusu come to Hong Kong. He wants "a real Chinese girl," "never out of fashion," and when she calls him a modern man he replies, "You say 'modern,' but what you probably mean is Western." Their uncertain budding relationship takes Liusu into territory as ambiguous and unsettling as being a widow in her mother's home, but with the frightening freedom of being more or less alone in a huge, unknown city.

Chang's writing is intensely visual, influenced by modernism while maintaining sparkling clarity. On Hong Kong's waterfront:

"it was a fiery afternoon, and the most striking part of the view was the parade of giant billboards along the dock, their reds, oranges, and pinks mirrored in the lush green water. Below the surface of the water, bars and blots of clashing color plunged in murderous confusion. Liusu found herself thinking that in a city of such hyperboles, even a sprained ankle would hurt more than it did in other places."

Her binocular vision (to borrow the the title of Edith Pearlman's collection, another straddler of worlds) is the kind of perspective I find endlessly fascinating. The invasion of Hong Kong has serious repercussions for Liusu and Liuyuan's future together. It's the sort of widening out, from the deeply intimate to the global, that I love to encounter in fiction and strive to achieve in my own work. I'm so glad I finally got to this novella and look forward to reading the rest of the collection. "The Golden Cangue," another novella in the volume, is translated by Chang herself--it'll be a real treat to get a sense of how she viewed her own work and how it should feel in English.

For more Women in Translation Month goodness, check out Meytal Radziniski's wonderful blog Biblibio.

Stay in the loop! Sign up here for a short & sweet monthly newsletter of upcoming events, publications, and tiny bits on art, food, cities, and literature. Like this blog, but less often and right in your inbox.

[mailchimp_subscriber_popup baseUrl='mc.us16.list-manage.com' uuid='f003e73335195658bffdce511' lid='45632cd706' usePlainJson='true' isDebug='false']

I first came upon Laia Jufrese's

I first came upon Laia Jufrese's  I adored the film Persepolis, based on Marjane Satrapi's graphic memoir of growing up during the Iranian Revolution. So when I stumbled upon

I adored the film Persepolis, based on Marjane Satrapi's graphic memoir of growing up during the Iranian Revolution. So when I stumbled upon  I'm happy to have my

I'm happy to have my

Despite everything, I need to celebrate 2017 on a personal level. Daughters of the Air, which I'd toiled over for years, finally came out, and people are reading it and telling me they are enjoying it! Michael and I celebrated the holiday season with candles and latkes and lights and dim sum and snow (!) and The Shape of Water (a beautiful love story!) and chocolate peanut butter pie and New Year's Eve back at the Hotel Sorrento's Fireside Lounge for reading (me, Teffi's Subtly Worded, him Hanna Krall's Chasing the King of Hearts, which I'm happily adding to my

Despite everything, I need to celebrate 2017 on a personal level. Daughters of the Air, which I'd toiled over for years, finally came out, and people are reading it and telling me they are enjoying it! Michael and I celebrated the holiday season with candles and latkes and lights and dim sum and snow (!) and The Shape of Water (a beautiful love story!) and chocolate peanut butter pie and New Year's Eve back at the Hotel Sorrento's Fireside Lounge for reading (me, Teffi's Subtly Worded, him Hanna Krall's Chasing the King of Hearts, which I'm happily adding to my  The day after

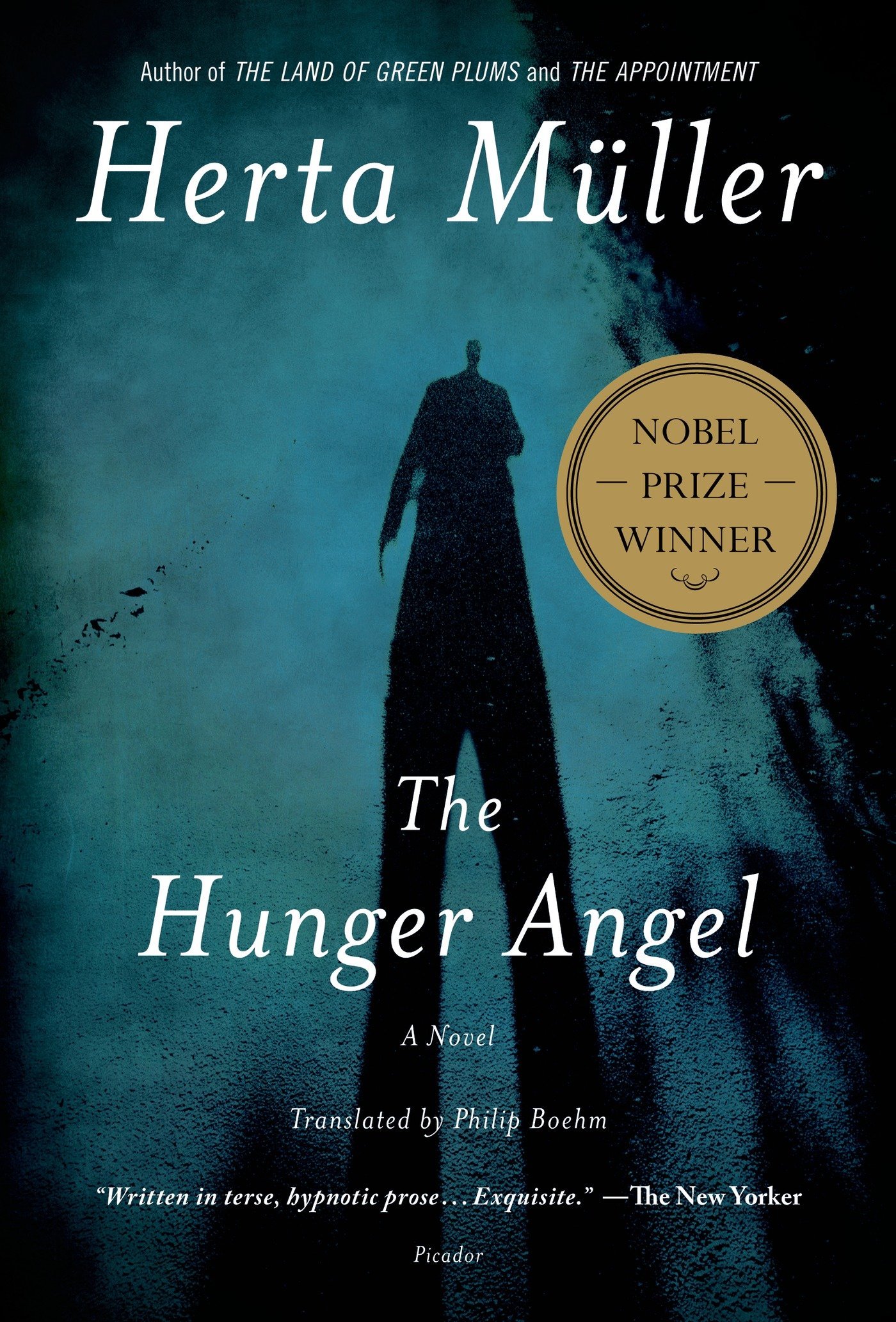

The day after After I read The Land of Green Plums a few years ago, Herta Müller joined a short list of authors whose work I want to read all of. I am not the sort of reader who methodically works through an oeuvre; I crave different voices. But this list includes Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, and Mavis Gallant. (It used to include Angela Carter; I adore her short fiction, but actually found trying to read her novels like trying to eat an entire chocolate mousse cake.) Müller's fiction is poetic and harrowing and sheds light on the country my family comes from. For me, she is a must.For my third installment of

After I read The Land of Green Plums a few years ago, Herta Müller joined a short list of authors whose work I want to read all of. I am not the sort of reader who methodically works through an oeuvre; I crave different voices. But this list includes Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, and Mavis Gallant. (It used to include Angela Carter; I adore her short fiction, but actually found trying to read her novels like trying to eat an entire chocolate mousse cake.) Müller's fiction is poetic and harrowing and sheds light on the country my family comes from. For me, she is a must.For my third installment of  August is

August is

The Seattle Public Library and Seattle Arts & Lectures launched

The Seattle Public Library and Seattle Arts & Lectures launched