By skin of my teeth I am getting this Women in Translation Month blog post out into the ether. I thought it would be cute to read Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season after reading Laurie Colwin’s A Big Storm Knocked It Over. Colwin’s essay collection Home Cooking was a great comfort to me and, not surprisingly, there was so much to love about her last novel, which is the first novel of hers that I read. At the same time, I can see issues of race in this 1992 novel that feel a bit out-dated, but I can relate to the protagonist’s anxiety as a Jew and her desire to belong.

The transition to Melchor’s 2016 novel Hurricane Season (translated in 2021 by Sophie Hughes) was not at all cute. That novel is as intense as its title suggests and then some. The chapters are long and devoid of paragraph breaks, creating textual claustrophobia as the cherry on top of the unrelenting anger, violence, misogyny, lust, and homophobia that wreaks havoc on a poor Mexican village where, at the opening of the novel, a witch has been murdered. The lack of paragraphs reminds me of László Krasznahorkai’s novel Satantango (trans. George Szirtes), another novel of unrelenting darkness, but that one moved like suffocating sludge, whereas Melchor’s novel is more propulsive (if also increasingly horrific in its violence). I would not recommend Hurricane Season to the faint of heart, but if you can handle a dark story that will get you outside of your comfort zone and show you a desperate corner of the world, and if you’d like to see how the author manages a different point of view in each chapter (with something of a dusky reprieve by the end), definitely check it out.

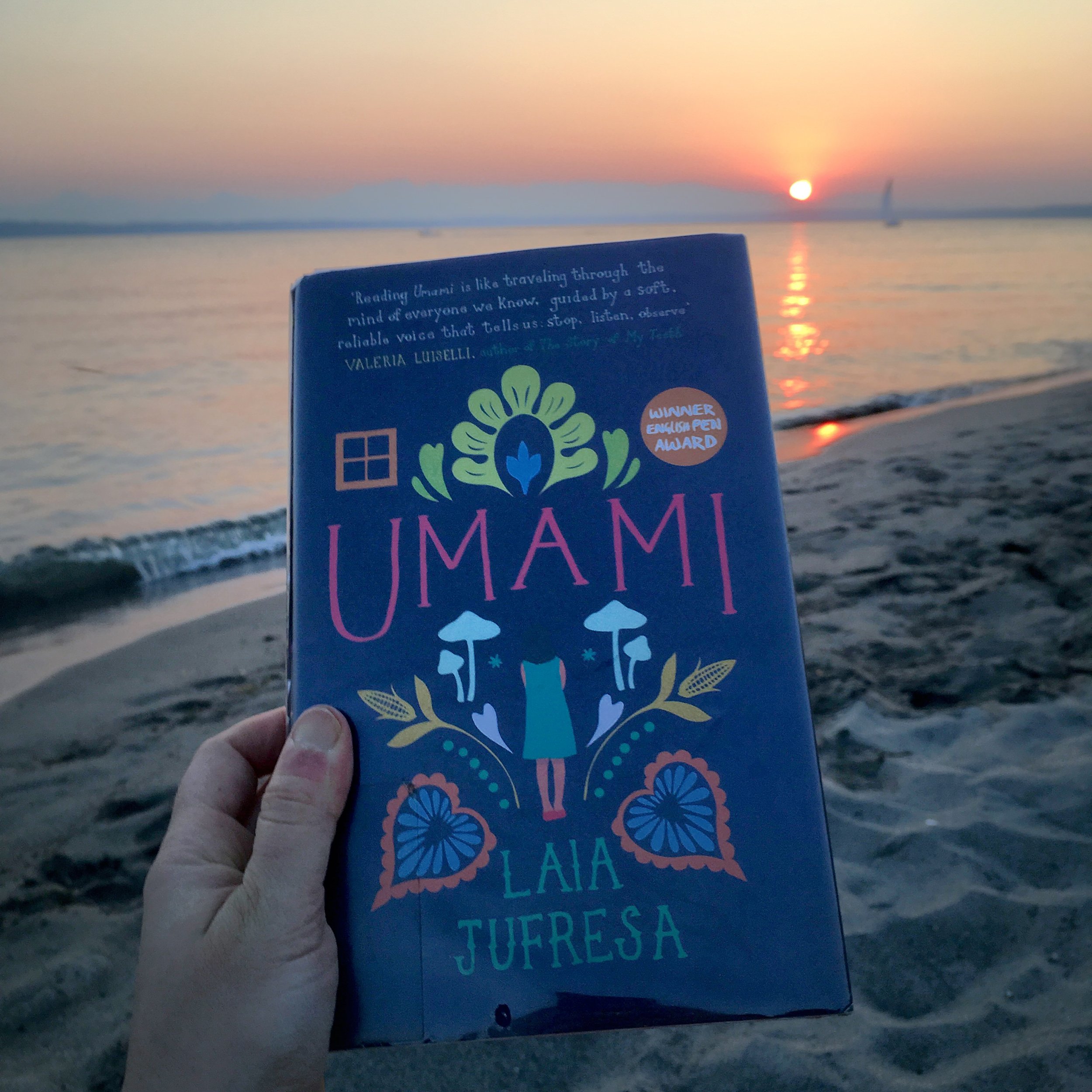

I first came upon Laia Jufrese's

I first came upon Laia Jufrese's